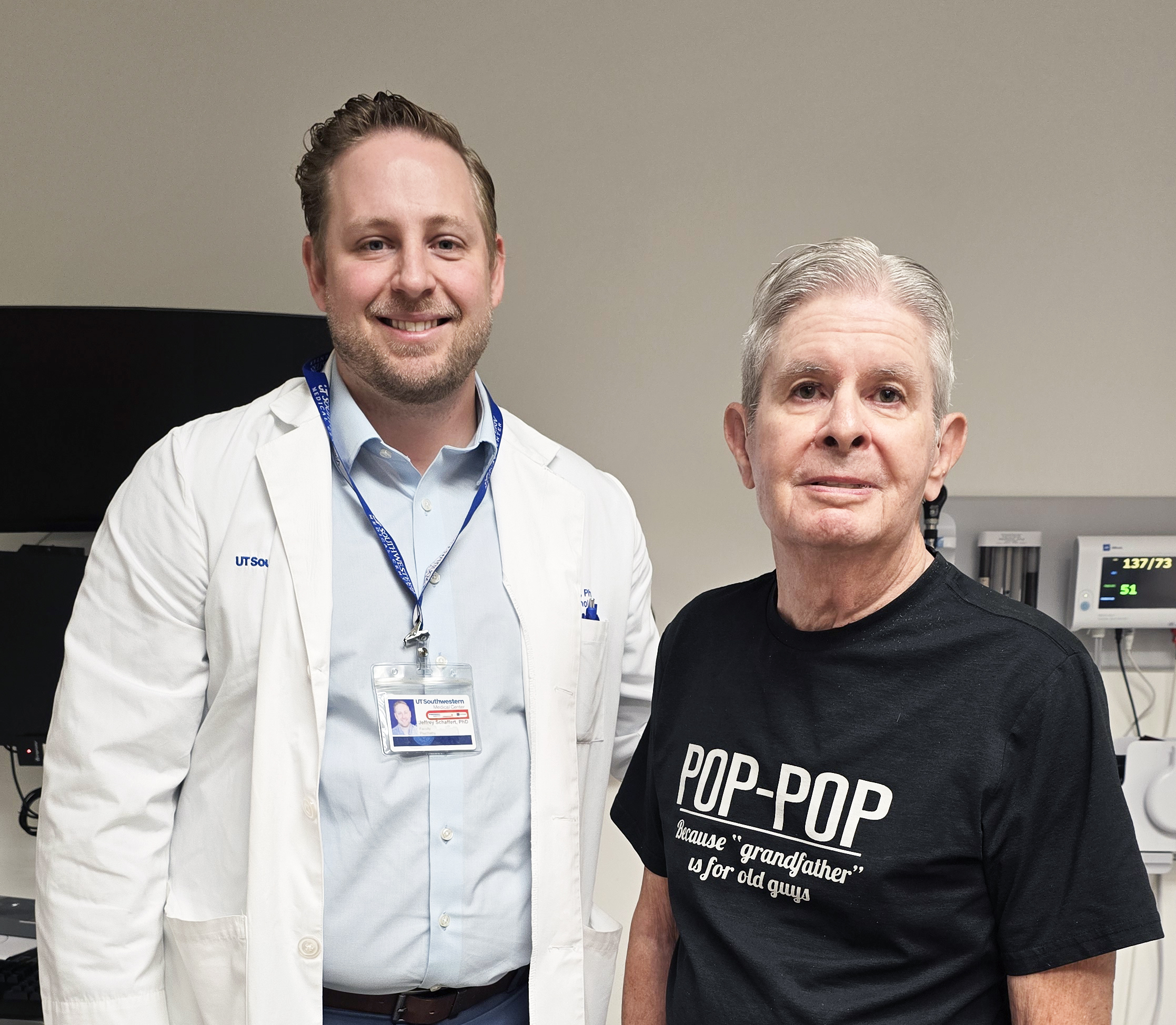

Jeffrey Schaffert, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and a Dedman Family Scholar in Clinical Care and Richard “Dick” Nash, patient

Richard “Dick” Nash first suspected something might be wrong in 2011, when he participated in a walk for juvenile diabetes in honor of his granddaughter. “It was only 2 miles – no big deal – but I wasn’t able to complete it without falling down,” he recalls. “My wife had to help me back to the car.”

After that day, Mr. Nash’s health only continued to deteriorate. His legs would stiffen involuntarily, his sense of balance worsened, and walking became increasingly difficult, if not impossible. His general movement slowed overall, and even his concentration felt sluggish, making everyday communication a challenge.

Eventually he sought out a neurologist and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Given his symptoms, this appeared to be the most likely cause. He began physical therapy and medication, hoping to regain some of his mobility and cognition.

But something still didn’t feel right for Mr. Nash.

Even though he had the hallmark signs of Parkinson’s – stiffness, slow movement, poor balance, cognitive issues, incontinence – many of the treatments prescribed to him didn’t really make a difference. His physical problems also seemed to change often.

“The symptoms were never consistent,” he says. “One day I’d feel one way, and the next day I’d feel another.”

Determined to find answers, Mr. Nash set out on a quest for an effective remedy to his problems. Over the next decade and beyond, he would cycle through numerous physicians and specialists, with almost no improvement. His condition worsened, until his journey led him to UT Southwestern’s doors. There, doctors at the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute uncovered a new diagnosis: normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), a rare condition caused by excess fluid accumulating in the brain.

What is Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus?

Typically seen in patients over age 65, NPH is characterized by an excess buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain. During normal processes, CSF is created constantly, cycles through the brain, and finally is reabsorbed into the body. When these processes are interrupted, extra fluid accumulates, compressing the brain and impairing its ability to clean itself. This can lead to:

- Mobility issues, particularly stiffness when walking

- Cognitive impairment, marked by confusion or forgetfulness

- Urinary incontinence

Unlike typical hydrocephalus, where patients have a significant increase in pressure on the brain, NPH patients show little or no pressure increases, making it harder to detect. Though it’s estimated that 800,000 people in the U.S. are affected, up to 80% of cases may go unrecognized. Due to its rarity and the similar nature of its symptoms, NPH is commonly misdiagnosed as different neurogenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

NPH is typically divided into two categories:

- Idiopathic NPH, where the exact cause is unknown, but usually attributed to aging issues disrupting how CSF is circulated in the body

- Secondary NPH, where the cause for CSF disruption can be traced to another medical condition, such as:

- Head injury

- Surgery complications

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding in the area around the brain)

- Brain tumors

- Brain infections (such as meningitis)

- Brain inflammation

NPH received a rare boost in the public spotlight in May 2025, when famed musician Billy Joel revealed his own diagnosis, canceling all scheduled performances to undergo treatment.

One Setback After Another in the Search for an NPH Diagnosis

With NPH, the search for answers isn’t always a quick one.

After the first signs of trouble at the juvenile diabetes walk, Mr. Nash’s functionality continued to decline. He finally saw a neurologist in 2016, but this was only the first of many physicians to come and go during his yearslong hunt for a proper diagnosis and treatment:

- His first neurologist ordered a CT scan, but then abruptly retired due to personal health problems before giving Mr. Nash a diagnosis.

- His next doctor did further, extensive testing and diagnosed Mr. Nash with Parkinson’s but could not determine the severity of his condition.

- Nash began seeing a movement specialist and attending various therapy programs, until his specialist left on maternity leave and then quit the clinic altogether.

As time passed, Mr. Nash grew increasingly skeptical about his Parkinson’s diagnosis. “I didn’t really think I had classic Parkinson’s,” he says. “I suspected I had NPH at this point, because I’d had two lumbar drains and neither one of them was conclusive.”

He sought out yet another specialist, hoping to get to the bottom of his condition. But after waiting six months for his first appointment, he was met with more discouragement when his new specialist promptly informed him they were leaving the clinic to start a private practice.

After bouncing between new health care providers for almost a decade, Mr. Nash was growing despondent as his illness became harder to manage. His leg stiffness worsened until he was mostly homebound, requiring a transport wheelchair anytime he left the house. His cognitive deficits also made it difficult to hold conversations or use the phone or computer. This in turn took a toll on his main caregiver, Sharon, his wife of more than 55 years.

“He had basically given up,” she recalls. “He didn’t want to live. He didn’t want to do anything, so his muscles had atrophied. He just was not motivated to care for himself.”

Fortunately, the answers Mr. Nash had been looking for were right around the corner, when a routine visit to a physical therapist at UT Southwestern brought the breakthrough he needed.

The Turning Point from Parkinson’s to NPH

While Mr. Nash’s last specialist couldn’t offer much in the way of clarity, they did refer him for help with his incontinence, another common Parkinson’s symptom. This led him to book an appointment at UT Southwestern with pelvic floor specialist Michelle Bradley, PT, D.P.T., WCS.

Like his previous health care practitioners, she initially didn’t see any reason to doubt Mr. Nash’s Parkinson’s diagnosis and began working with him to ease his symptoms. It wasn’t until Mr. Nash arrived for a later appointment in a wheelchair that she suspected something else might be going on.

“He told me he had a procedure a couple of days earlier that required valium. Since then, he’d had great difficulty walking but attributed it to the medication,” she says. “Knowing valium does not cause such a quick and long-lasting decline, I was concerned.”

The next time she saw Mr. Nash, he was even worse than before – still bound to a wheelchair and needing assistance to transfer to the treatment table. Even for Parkinson’s, such a rapid degeneration in a short period of time is unusual and raised a major red flag.

She was so concerned that she scheduled him to be seen by someone from UTSW’s team of NPH specialists.

For the first time in years, Mr. Nash felt someone truly saw what he was going through.

The First Steps to an NPH Diagnosis

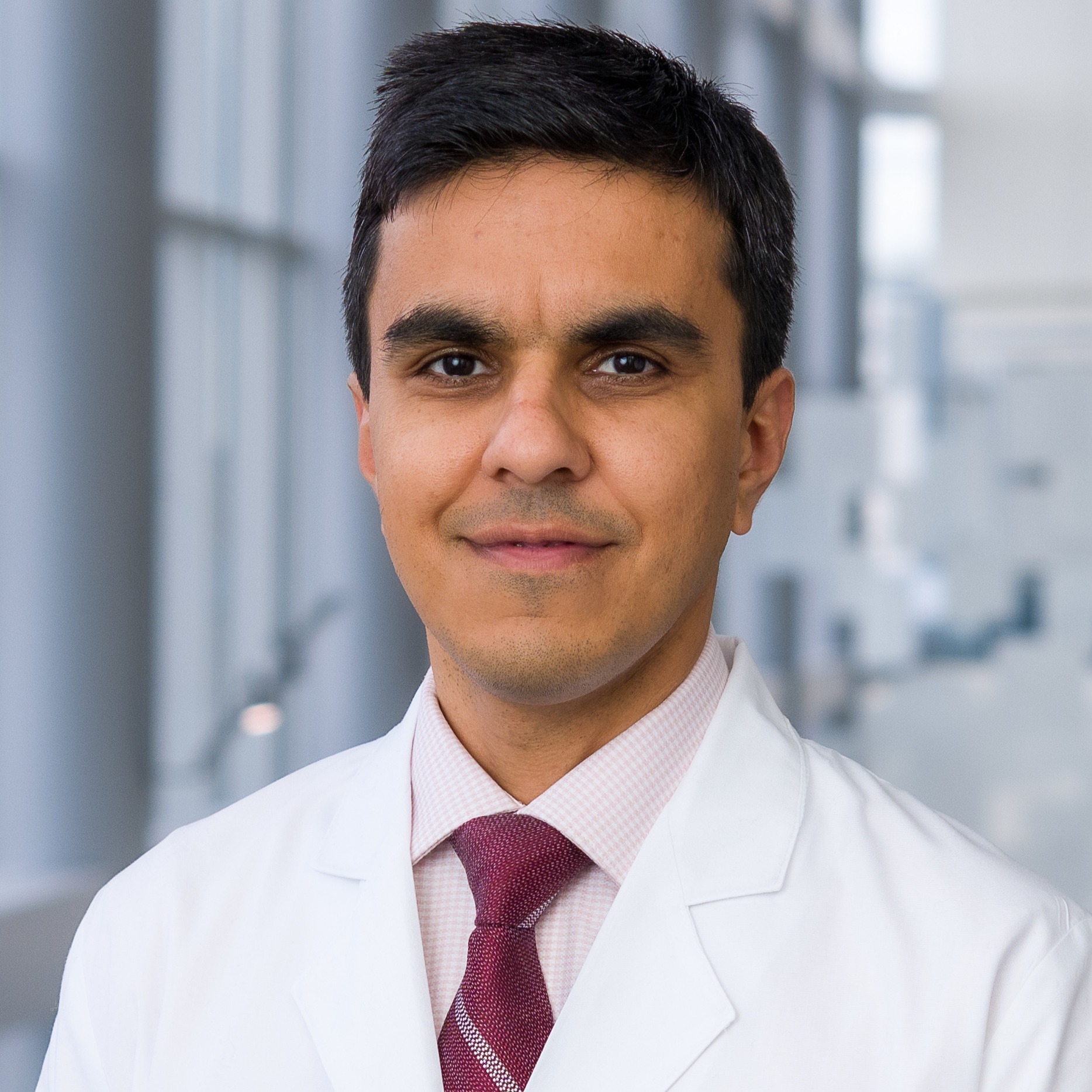

Vibhash Sharma, M.D.

Before Mr. Nash could begin a new treatment plan, he needed a neurologist to confirm that NPH was a likely cause for his symptoms.

For this, Mr. Nash next met with Vibhash Sharma, M.D., Medical Director of the Interventional (Neuromodulation) Movement Disorders Clinic and Associate Professor of Neurology. After a thorough evaluation, Dr. Sharma ruled out the initial Parkinson’s diagnosis, despite some similar symptoms. Even though Mr. Nash’s legs would freeze up and cause him to fall, he still had not developed other conditions consistent with the disease after several years of illness.

“I would have seen other findings, such as rigidity and clear bradykinesia, on exam if his gait difficulty was from Parkinson’s,” Dr. Sharma explains.

During the course of his treatment, Mr. Nash had also been prescribed levodopa, a standard Parkinson’s medication that boosts dopamine levels in the brain. After several months though, it appeared to have no effect on his symptoms. A past dopamine transporter (DaT) scan similarly failed to show strong evidence of Parkinson’s. A recent MRI scan, however, had revealed findings more consistent with NPH. Based on the imaging and his own clinical exam, Dr. Sharma referred Mr. Nash to the NPH group at UT Southwestern.

The Right Team for the Right Diagnosis

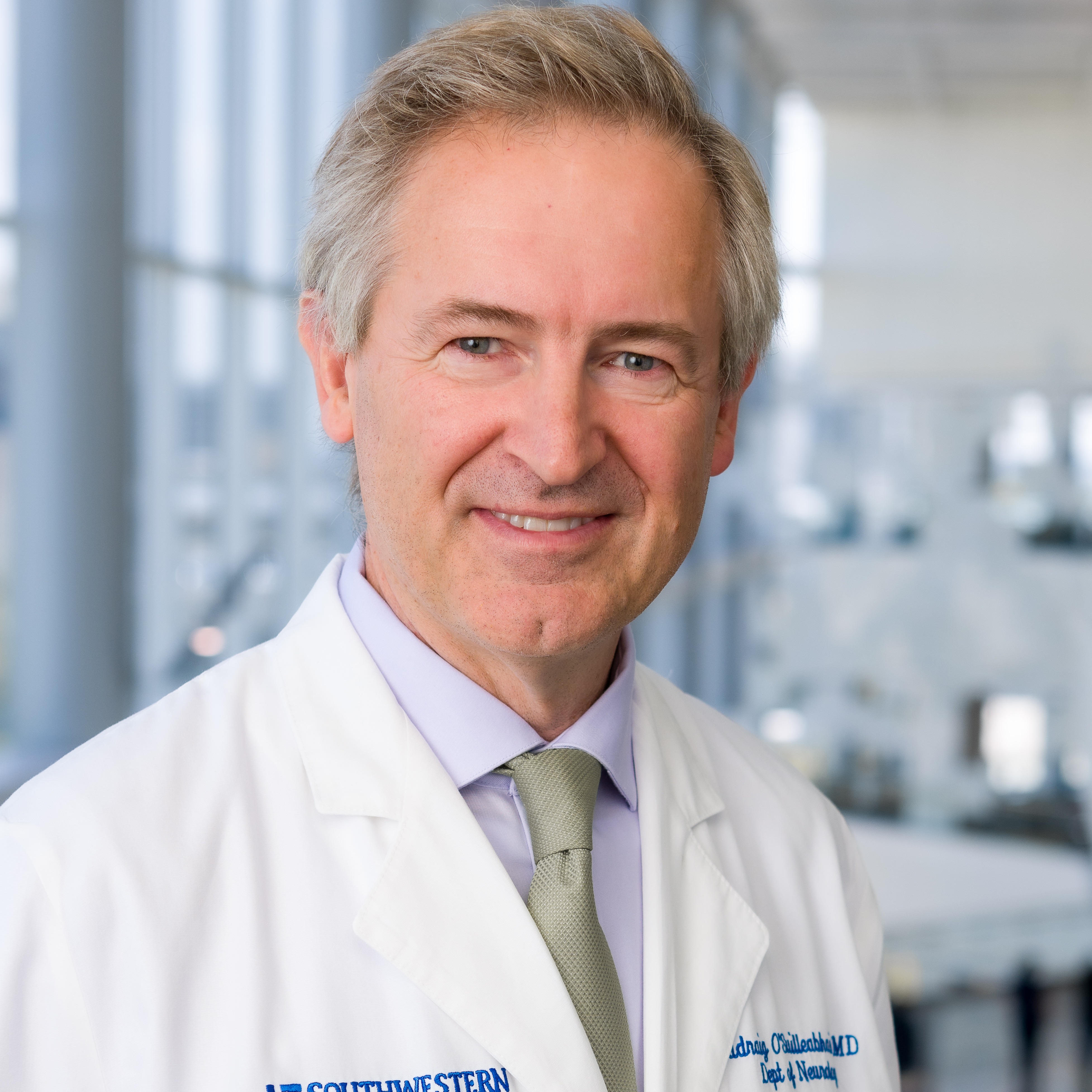

Padraig O’Suilleabhain, M.D.

In February 2024, Mr. Nash finally reached UT Southwestern’s dedicated NPH team. The group consists of several neurology specialists, including Padraig O’Suilleabhain, M.D., Professor of Neurology, and Jeffrey Schaffert, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and a Dedman Family Scholar in Clinical Care.

While many neurologists encounter NPH through their clinical practice, UT Southwestern’s physicians have taken a more focused approach, forming a dedicated interdisciplinary team to tackle potential NPH cases that come through the Medical Center. By combining their expertise, the team can identify subtle signs of NPH more easily in patients, streamline their care, and hopefully bring clarity to a notoriously ambiguous condition.

Given Mr. Nash’s symptoms and past testing, the team was not particularly surprised that he had received a Parkinson’s diagnosis. Once the team set to work unraveling his extensive medical history and performing their own evaluations however, they noted even more concerning evidence of NPH.

- Clinical symptoms

Along with the evidence identified by Dr. Sharma, the NPH team delved deeper into the initial symptoms that brought Mr. Nash to their clinic.

His walking and balance difficulties fit the pattern of other NPH patients, as Dr. O’Suilleabhain explains: “His walking difficulty had what we call ‘magnetic gait,’ where the tendency is for his feet to kind of stick to the ground as though there were magnets in his shoes. It’s a classic gait complaint, and it had deteriorated over the course of 10 years or so.”

Mr. Nash’s negative DaT scan and the fact that he hadn’t responded to levodopa concerned Dr. Schaffert.

“Typically, patients respond well to that,” he says. “If you suspect a patient has Parkinson’s, you give them that medication. If they get a lot better, that almost confirms the diagnosis. The fact that he didn’t get better kind of raises a yellow flag of ‘What else could we be dealing with?’”

The fluctuations in the severity of Mr. Nash’s symptoms were less definitive, but also added to the potential evidence for a new diagnosis.

“It’s certainly common for people to feel their brain operating differently at times, both physically in terms of how they walk and cognitively in how clearly they’re thinking,” Dr. O’Suilleabhain says. “Sleep, caffeine, blood pressure, and even the weather can have an effect. Parkinson’s symptoms can change in severity as neurons are lost, but the variation in CSF outflow that NPH causes produces a similar effect.”

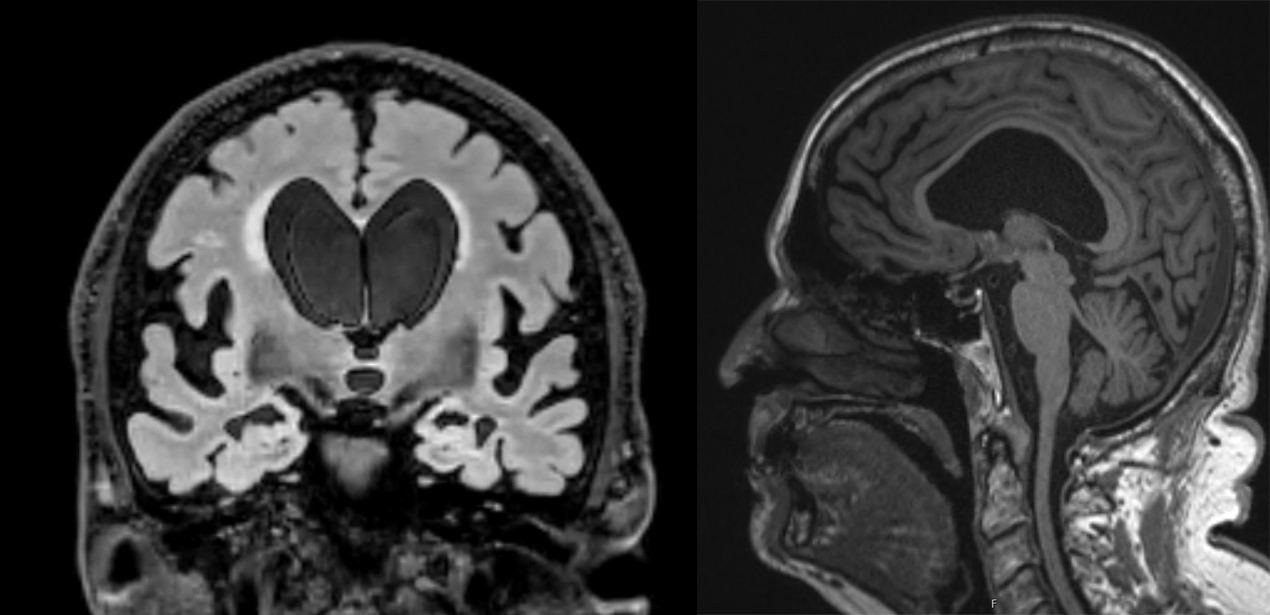

Brain scans showing expanded ventricles in the middle of the brain and evidence of disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid space hydrocephalus (DESH).

- Imaging

From the look of his scans, the ventricles in the middle of Mr. Nash’s brain had enlarged a significant amount. In hydrocephalus patients, this is typically caused by excess CSF pressure, which stretches and expands the ventricles over time. Theoretically, this could be the reason for NPH patients’ issues with walking and balance. Since the ventricles are closely tied to the corticospinal tract, which connects to the spine, the expanded ventricle could disrupt communication between the brain and the legs.

Mr. Nash’s imaging also showed evidence of disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid space hydrocephalus (DESH), where CSF is trapped and accumulates in the sulci (grooves or furrows of the brain), creating widening spaces that press on the brain. On scans, a space like this can look like brain shrinkage, which may have contributed to Mr. Nash’s earlier misdiagnosis. While not integral for an NPH diagnosis, DESH is one of the more specific diagnostic features of idiopathic NPH – it even plays a strong role in Japan’s clinical diagnostic guidelines.

- CSF drains

One key detail the team noted was that Mr. Nash had already completed two lumbar spinal taps over the course of his illness. During these procedures, a small needle or catheter is inserted into the lower back to remove some of the fluid around the spinal cord. Draining a small amount of CSF can sometimes relieve symptoms on its own, giving doctors another clue to their patient’s condition.

“The idea of doing a spinal tap or drain trial to pull out fluid in the spine is essentially to see if by relieving just a little bit of that compression, perhaps we see improvement,” Dr. Schaffert explains.

In Mr. Nash’s case, each spinal tap lasted less than a day, with doctors removing 30-40 milliliters (mL) – about 6-8 teaspoons – of CSF all at once. Considering the average adult normally has 150 mL in their brain, he was already losing more than one-fifth of his CSF each time. And still, the results were inconclusive. At that point, Mr. Nash’s past doctors dropped the idea of any further CSF taps.

The NPH Diagnosis Gap

Unfortunately for patients like Mr. Nash, misdiagnosis is frequent for individuals with NPH.

Unlike cognitive conditions that can be identified by certain markers, such as amyloid for Alzheimer’s disease, NPH lacks a definitive test, and comorbidities can further muddy the waters. Diagnosis often requires a process of elimination through various treatments before physicians can prescribe more targeted care. It also can’t be tested as easily as other hydrocephalus conditions, since it isn’t always clear what leads to an excess of CSF. This means patients typically must undergo CSF taps, drains, medication, and potentially surgery before their physicians can reach an NPH conclusion.

The medical community seems to be catching on that NPH could be more prevalent among older populations than previously thought. Researchers in Sweden recently studied brain MRI scans from a group of 70-year-old patients and found 1.5% showed evidence of NPH. A follow-up study showed 3% had NPH by age 77 in that same cohort, with around 65% converting to symptomatic NPH who had radiological evidence. An earlier study also revealed a significantly higher prevalence in individuals over age 80. It’s possible NPH could account for a much larger proportion of dementia and mobility issues among older groups.

This is one of the reasons why specialists at UT Southwestern have taken an interest in NPH in the past couple of years. “We’re trying to be more systematic about how we make an NPH determination,” Dr. O’Suilleabhain says.

He theorizes an outflow resistance problem may be the fundamental source of NPH, which would explain why NPH patients often show normal pressure levels during testing. Their cerebrospinal fluid may be flowing fine most of the time, but once a blockage of some sort prevents it from dissipating into the body, the pressure spikes and doesn’t go back down for some time. For some NPH cases, this blockage could be located in the meninges between the skull and the brain, but this has been difficult for researchers to study because the meninges are usually damaged during an autopsy.

One Last Test for NPH

Jonathan White M.D.

For the NPH team, the question remained if Mr. Nash was a good candidate for the next stage of treatment: surgery to install a shunt.

To help make that decision, the team consulted with expert neurosurgeon Jon White, M.D., Professor of Neurological Surgery and Radiology and holder of the Mitch Hart Distinguished Professorship in Neurosurgical Innovation at UT Southwestern. Despite the signs pointing to NPH, there still wasn’t enough evidence to conclude that a shunt would even relieve Mr. Nash’s symptoms. To make the final determination, the team proposed one more CSF drain along with a lumbar infusion test, a much more extensive diagnostic procedure not offered by many clinics.

This time, Mr. Nash was admitted to William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, where he was placed on a spinal tap for four days straight. Every four hours, doctors drained 20 mL of CSF, essentially removing half of what the body produces regularly and forcing the brain’s fluid systems to reset. Mr. Nash reported some improvement in his walking and cognition, but like his previous drain tests, the results weren’t definitive enough to justify surgery.

During the same hospital visit, however, doctors also performed a lumbar infusion test. Unlike a CSF drain, a lumbar infusion test doesn’t just reduce pressure but actively tests how well CSF flows and is absorbed by the brain. Rather than only draining cerebrospinal fluid, the physician slowly adds a small amount of sterile fluid, while sensors monitor the intracranial pressure (ICP) in real time. By studying how the CSF pressure changes over time, doctors can observe how well the body is absorbing cerebrospinal fluid.

During the test, the team noted two concerning results:

First, Mr. Nash’s ICP rose significantly during the infusion. His baseline started at 12 mmHG, which was right in the normal range of 5-20 mmHG. After infusion, his ICP more than doubled to 30 mmHG – especially alarming since most people don’t go above 20 mmHg during tests.

Second, as they added fluid to his system, his ICP began to spike during each heartbeat. Normally, doctors will see a small wave of pressure with each pulse during the test, but Mr. Nash’s ICP was elevated during pulses at the beginning of the test and continued to climb until the end.

All this pointed to a compromised system in the brain and explained why Mr. Nash experienced changing symptoms. Along with his imaging and clinical symptoms, this was the final piece the doctors needed. They now had enough evidence to diagnose Mr. Nash with NPH and support installing a shunt.

At long last, Mr. Nash’s suspicions were confirmed. But even with an NPH diagnosis, there was no guarantee a shunt would help, and surgery sounded daunting.

“I wasn’t real excited about having holes drilled in my head,” Mr. Nash recalls from his meeting with Dr. White. “But he seemed confident this would probably help.”

After discussing the procedure together, Dr. White and Mr. Nash set a date for the surgery.

Relieving the Pressure

On Aug. 1, 2024, Mr. Nash arrived at Clements University Hospital for his scheduled surgery.

It had been a long road to this moment. In Mr. Nash’s eyes, this would be his last shot at recovering any of the life he’d had before his illness. He had already made up his mind that if this procedure didn’t work, he would finally give up. He would stop pursuing more treatments and just live out the rest of his days in hospice. After years of setbacks and uncertainty, he was ready to let go.

That day, Mr. Nash received a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, requiring two surgical teams – one to install the shunt into his skull and one to connect it to a drain in his abdomen. The shunt was inserted into his brain ventricles, where the fluid appeared to accumulate the most. For the second part of the procedure, a long, thin tube was connected to the shunt and threaded through his neck and chest to the peritoneal cavity, a space in the abdomen that houses digestive organs.

Once the procedures were completed, the shunt would act as a pressure relief valve, opening to release CSF when the pressure in Mr. Nash’s ventricles was too high. The CSF would then flow down the tube into his abdomen to be absorbed by the body. Once the pressure dropped down to a normal range, the shunt would close again, stopping the flow of CSF. This enabled the fluid to bypass any blockages, stabilized the fluid pressure, and restored the brain’s regular cleaning functions.

All that remained was to see if this final step would make a difference.

From NPH to Rebirth

After shunting, most NPH patients don’t see a significant difference for weeks or even months. For Mr. Nash, the change was almost immediate.

Just one day after his surgery, he did something he hadn’t done in years: He got out of bed and walked 250 steps with a walker. It was, quite literally, the biggest step forward in his recovery in several years.

Describing it as his “day of rebirth,” Mr. Nash has been determined to stay healthy ever since. More than one year later, he averages about 3 miles of walking daily and has regained much of the functionality he thought he had lost forever. At 79, he’s able to do more than he could almost 10 years ago.

“I can operate in the kitchen now,” he says. “I can go out when people invite me to leave the house. Sharon and I go out when we want to see a movie, and I walk with a cane. She tells me I walk faster than I used to.”

As part of his recovery, Mr. Nash began speech therapy, which helped him regain the socializing he had lost during his illness.

“One of the things that happens when you have an illness like he had, you become isolated,” Mrs. Nash says. “And the more isolated you become, the more cognitive deficits you develop. He’s just so much better. Now he’s able to converse with people and do a lot of things that he just wasn’t able to do before his surgery and before the therapy.”

Other symptoms have faded too, including the incontinence that inadvertently put him on the path to healing.

“I don’t wear what we call ‘traveling pants’ anymore. Used to be when I left the house, I had on my traveling pants,” Mr. Nash says. “I also reduced my medication by about 60% – got rid of excess carbidopa and a lot of other pills I don’t need anymore.”

Of everything he’s gained over the past year though, he’s most proud of a photo with his great-grandson. “That picture represents four beneficiaries of my operation,” Mr. Nash says. “There’s myself, my wife, my family, and UT Southwestern. Dr. Schaffert, Dr. White, and Dr. O’Suilleabhain are heroes, because they did what was necessary. They listened to me.”

The Future of NPH Diagnosis and Treatment

The NPH team at UT Southwestern hopes to better understand the disease to provide more efficient diagnosis and treatment. While lumbar drains continue to be a factor in diagnosis, the team hopes to move away from such invasive testing to a more streamlined array of cognitive and mobility tests. Physicians also hope to improve methods for distinguishing NPH from other conditions, such as Alzheimer’s.

Since starting this process, UT Southwestern’s clinical research registry that has seen over 250 patients thus far, with the infrastructure being used to help support pilot funding from the Hydrocephalus Association to investigate neuropsychological presentations of NPH.

Additionally, Dr. Schaffert has received an endowed Dedman Family clinical research position to investigate the mechanisms and prognosis of cognitive impairment in NPH through advanced diffusion weighted imaging and fluid biomarkers. As principal investigator, Dr. Schaffert was also awarded a grant from the Texas Alzheimer’s Research Care and Consortium to use plasma to better diagnosis comorbid Alzheimer’s in those with suspected NPH to improve diagnostic and prognostic accuracy.

UT Southwestern recently participated in the Placebo-Controlled Efficacy in Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (iNPH) Shunting (PENS) trial. This multicenter randomized controlled double-blind trial, published in 2025, proved the efficacy of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) in treating NPH, after decades of accumulating evidence from case series and smaller trials. While shunting clearly improves functionality in many patients, understanding its full effects on cognition and mobility could help doctors determine which patients are most likely to benefit.

Researchers are also experimenting with new, less-invasive shunt techniques. The eShunt System, for example, only requires an outpatient procedure and can be installed on a patient’s groin instead of drilling into the skull, draining CSF directly into the bloodstream.

After his own experience, Mr. Nash’s main hope is that NPH will gain more recognition in the medical community so others with incorrect diagnoses can get the treatment to regain their lives as he did. “Miracles do happen,” he says. “And I was the beneficiary of a miracle.”